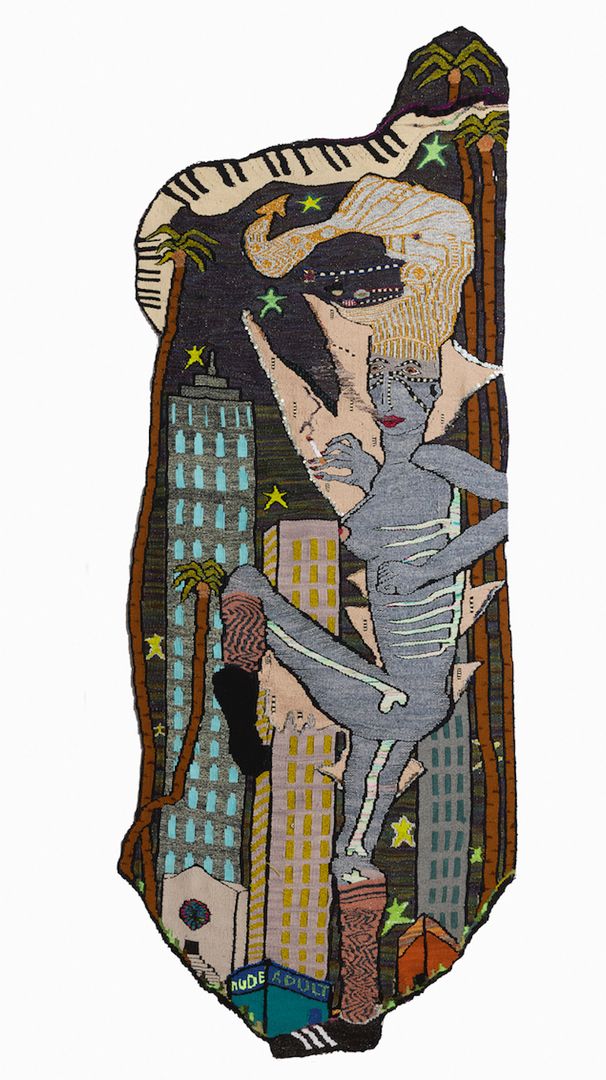

Slave Labour

I hear a lot about how slavery was 100 years ago. But right now, at this moment, there are approximately 40 Million people (world wide) that are trapped in slavery. This painting is about a slave master, using forced labour to mass produce clothing. In the background a Banksy illustration of this issue. Part of our Electronica Series, about people and their devices.

Responses (1)

January 28, 2022

Phil Dynan’s "Slave Labour" is a hard but necessary pill to swallow. It explicitly highlights one of the most brutal, disguised, and difficult to accept truths about our society. There is almost zero ethical consumption available to us. He brilliantly fills the picture with evocative material reminders of the problem's pervasiveness.

The slave-like working conditions behind almost all our many things is an uncomfortable subject, but one of the essential roles of great art is to make us reflect on what we would otherwise ignore. From head to toe, children's toy to adult trinket, phone to computer, bedsheets to wedding ring, and so on ad infinitum, most of what we own was, at some point of its construction, the product of criminally exploitive labor. We try and comfort ourselves with companies' acts of performative altruism. We buy a pair of Nikes because the brand took a political stance we approve of or because some small portion of the profits goes to fighting the AIDs pandemic, but what use is all this virtue-signaling when the shoes are made in unimaginable conditions by enslaved children in south-east Asia? There is a use, and the use is cyclical: companies can continue to produce their products in abjectly evil ways, and we can feel good about buying their barbarically manufactured products. Companies and consumers have established a tacit agreement to ignore the cruelty inherent in almost any purchase.

We never really got rid of slavery, child labor, or 18-hour workdays; we just exported them. Instead of 12-year-olds in the west working 18-hour days to make our clothes, Indonesian children work 18-hour days making our clothes. Our improvements look a lot more like a reshuffling than an actual change. We disguise the uninterrupted barbarism of unregulated worker exploitation under a veil of our faux political and humanitarian accomplishments, surface level and ultimately insignificant acts of corporate charity (which we are invited to take glorious part in with our many purchases), and comforting PR stunts that prove the company is on the right side of history. Some of us buy a brand of beans because the company has expressed some ideological principles we agree with. Others refuse to ever so much as look at those beans again. But we all prefer to ignore that whatever bean company we choose almost certainly relies on wildly exploitive labor to create the tins and harvest the beans. These are all just performances we willingly buy into, so we do not have to confront the unassailable fact that most of our consumption is unethical.

I don’t write this from a moral high ground. A pair of brand-new Nikes just arrived in the mail, and I can’t wait to wear them. I am no better than anyone else in this matter, and, frankly, I am not sure I know how to be. What other options do we have? Sure, there are probably costly garments made entirely morally, but barely anyone can afford them. There are no cellphones or computers whose chips do not derive from minerals mined in the worse conditions in Africa. Can we be expected to live without technology, hunt and farm all our food, and wear clothes we made from scratch or purchased at a premium? We most certainly cannot, and the unreasonableness of that expectation is one of the main lynchpins to keep the system of exploitation in place. We can accept that all the pretensions of righteousness by major companies are a mirage. We can consume their products (as we usually have no alternative) but not accept their narratives of altruism. Ethical consumption may not be possible, but informed consumption is. As humans, we naturally want to find a good guy, but there is no good guy in the arena of large consumer corporations. And that will never change if we refuse to recognize it.

Dynan pulls no punches with "Slave Labour"; from its name to the visual elements it contains, everything is laid bare. The phone the gold and white-robed modern-day enslaver holds to his ear is the product of vicious exploitation. So too, with his kaleidoscopic sneakers and ostentatious sunglasses. He stands unconcerned and unembarrassed in front of Banksy’s archetypal depiction of one of his "employees". The Union Jack centers the picture and brings together the cycle of exploitation and consumption. The United Kingdom’s flag—a source of pride to many and unabashed imperialism to more—reminds us of the destination of the children’s work.

January 28, 2022

Great editorial. I know my piece does create some pain, depending on how much thought you give it. But my primary purpose for this piece (which is a part of a large set of paintings) is to document the use of electronic devices in this time period. Eventually, that iPhone will appear as ridiculous as the original "wire" phone. I DO also hope that the piece will cause some thought about our exploitation of slave labour.

February 08, 2022

That's really interesting Phil, I'm seeing it through a new lens now. I could do another few pages on the ubiquity of electronic devices.

- Category

- Digital Age, Historical and Political

- Type

- Painting - Unframed

- Materials

- Acrylic, Canvas

- Dimensions

-

36.00 inches wide

48.00 inches tall

2.00 inches deep - Weight

- 12.00 lbs

- Location

- Corning, CA, US